August 2001

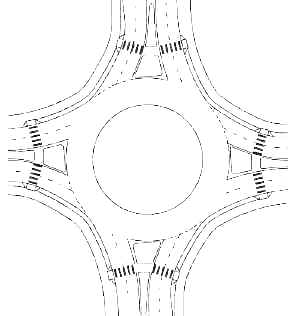

Figure 1. Chief Okemos Roundabout (Okemos, Michigan)

Photo courtesy of Dave Sonnenberg, Director of Traffic and Safety,

Ingham County, Michigan Road Commission

Roundabouts are replacing traditional intersections in many parts of the U.S. This trend has led to concerns about the accessibility of these free-flowing intersections to pedestrians who are blind and visually impaired. Most pedestrians who cross streets at roundabouts use their vision to identify a ‘crossable’ gap between vehicles. While crossing, they visually monitor the movements of approaching traffic and take evasive action when necessary. Blind pedestrians rely primarily on auditory information to make judgments about when it is appropriate to begin crossing a street. Little research has been conducted about the usefulness of such non-visual information for crossing streets at roundabouts. Recent research sponsored by the Access Board, the National Eye Institute, and the American Council of the Blind suggests that some roundabouts can present significant accessibility challenges and risks to the blind user (for a link to an abstract of this research, see the Resources section at the end of this document). This bulletin:

- summarizes orientation and mobility techniques used by pedestrians who are blind in traveling independently across streets;

- highlights key differences between roundabouts and traditional intersections with respect to these techniques;

- suggests approaches that may improve the accessibility of roundabouts to blind pedestrians; and

- encourages transportation engineers and planners to implement and test design features to improve roundabout accessibility.

MODERN ROUNDABOUTS

There are an estimated 40,000 modern roundabouts worldwide, and more than 200 have been constructed in the United States. Most of these have been built within the last 5 years. Many jurisdictions are now considering roundabouts to improve vehicle safety, increase roadway capacity and efficiency, reduce vehicular delay and concomitant emissions, provide traffic-calming effects, and mark community gateways.

A typical modern roundabout (Figures 1 and 2) is an unsignalized intersection with a circular central island and a circulatory roadway around the island. Vehicles entering the roundabout yield to vehicles already on the circulatory roadway. A dashed yield line for vehicles is painted at the outside edge of the circulating roadway at each entering street. The dashed line defines the boundary of the circulatory roadway (not to be confused with a conventional ‘stop bar,’ since there is not requirement to stop prior to entering the roundabout).

Figure 2. Typical urban double-lane roundabout

from Roundabouts: An Informational Guide (FHWA)

Roundabouts have raised or painted splitter islands at each approach that separate the entry and exit lanes of a street. These splitter islands are designed to deflect traffic and thus reduce vehicle speed. Splitter islands also provide a pedestrian refuge between the inbound and outbound traffic lanes.

Roundabout design in the U.S. has not yet been standardized, although several types have been defined in industry publications. Engineers use a variety of design techniques, mostly geometric, to slow vehicles as they approach or exit a roundabout. Differing design practices in Europe and in Australia continue to influence U.S. engineers as they refine design approaches for application in urban, suburban, and rural areas.

Studies conducted in western Europe, where roundabouts are common, and in the U.S. have generally found that roundabouts result in less severe vehicular crashes than more traditional intersections. This reduction in the rate of serious vehicular crashes is the most compelling reason cited by transportation engineers for the installation of roundabouts. Roundabouts increase vehicular safety for two main reasons: 1) they reduce or eliminate the risk arising at signalized intersections when motorists misjudge gaps in oncoming traffic and turn across the path of an approaching vehicle; and 2) they eliminate the often-serious crashes that occur when vehicles are hit broadside by vehicles on the opposing street that have run a red light or stop/yield sign.

The research findings on pedestrian safety at roundabouts are less clear. There have been relatively few studies, mostly conducted in Europe, concerning pedestrians and roundabouts. Pedestrian-vehicle crashes, the most commonly used dependent measure in pedestrian safety studies, tend to occur infrequently both before and after an intersection is converted to a roundabout. As a result, it is difficult to draw firm conclusions from the literature regarding pedestrian safety and roundabouts. One issue that is often not considered in pedestrian research is the degree to which pedestrian volume changes when intersections with signal or stop-sign control are converted to roundabouts. There is a need for research on this topic as well as a broad range of other pedestrian-related concerns at roundabouts. Little is known about the effect of roundabouts on older pedestrians, children, and pedestrians with disabilities. Anecdotal evidence indicates that many Australian engineers (who have extensive experience with roundabouts) consider these intersections to be unsuitable if large numbers of pedestrians are present.

The differences between modern roundabouts and traditional intersections controlled by traffic signals and stop signs have important implications for blind pedestrians. While some of these implications are not yet well understood, they must be considered by any transportation engineer or planner whose goal is to create an accessible pedestrian environment.

Improvements for wayfinding

- well-defined walkway edges

- separated walkways, with landscaping at street edge to preclude prohibited crossings to center island

- tactile markings across sidewalk to identify crossing locations

- bollards or architectural features to indicate crossing locations

- detectable warnings (separate at splitter islands) at street edge

- perpendicular crossings ; where angled, use curbing for alignment cues

- high-contrast markings

- pedestrian lighting

|

CROSSING AT TRADITIONAL INTERSECTIONS

The techniques and cues used by blind pedestrians crossing at traditional intersections are diverse and vary by location and individual. Many blind pedestrians have received instruction in using these techniques from orientation and mobility (O&M) professionals. In the most common technique for crossing at fixed-time signalized intersections, pedestrians who are blind use traffic sounds to align themselves properly for crossing and then begin to cross when there is a surge of through traffic next to and parallel to them. This occurs at the onset of the walk interval, when the traffic signal changes in the pedestrian’s favor. Cues that can be used for identifying that a street is just ahead, and for determining when to cross, include traffic sounds, the orientation and slope of curb ramps, textural differences between the street and sidewalk, detectable warnings underfoot, locator tones at pedestrian pushbuttons, and audible or vibrotactile information from accessible pedestrian signals (APS).

Key street-crossing tasks for the blind pedestrian include:

- detecting the intersection;

- locating the crosswalk and aligning the body in the direction of the crosswalk;

- analyzing the traffic pattern;

- detecting an appropriate time to initiate the crossing (at signalized intersections, determining the onset of the walk interval);

- remaining in the crosswalk during the crossing;

- monitoring traffic during the crossing; and

- detecting the destination sidewalk or median island.

When traffic sound cues are absent (e.g., when there are no cars on the street parallel to the pedestrian’s line of travel, and thus no auditory cue that the signal has changed) or unpredictable (e.g., when the intersection is of a major and minor street, and traffic signals are actuated by vehicles), information may be insufficient for determining the onset of the walk interval. In such situations, APS systems may be necessary. New guidance on the use of APS appears in the 2000 edition of the Manual of Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD).