Justice for All: Designing Accessible Courthouses

Recommendations from the Courthouse Access Advisory Committee

This report contains recommendations of the Courthouse Access Advisory Committee for the U.S. Access Board’s use in developing and disseminating guidance on accessible courthouse design under the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Architectural Barriers Act. This is not a regulation.

Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Members of the Courthouse Access Advisory Committee

- I. Introduction

- II. Recommendations for Accessible Courthouse Design

- III. Recommendations for Accessible Court Suite Design

- IV. Access to Raised Elements in Courtrooms and Courthouses

- V. Recommendations for Outreach and Marketing of Information on Accessible Courthouse and Courtroom Design

- VI. Background

- Appendices

Acknowledgements

The Courthouse Access Advisory Committee is grateful to the many organizations and individuals who participated in its meetings and provided comment and insight on different aspects of courthouse accessibility. The real-world experiences shared by those involved in courthouse management and design, accessibility, and disability rights were valuable to the Committee’s information gathering efforts.

The Committee toured courthouses in different cities as part of its quarterly meetings. These tours were extremely beneficial to the Committee’s work by illustrating how accessibility has been addressed in a various types of courthouses. The Committee appreciates the cooperation and hospitality of those who arranged and conducted these tours, including justices, court managers, facility operators, and architects associated with the:

- City of Phoenix Municipal Courthouse

- Sandra Day O’Connor U.S. Courthouse in Phoenix

- Superior Court of the District of Columbia

- District of Columbia Court of Appeals

- Cook County Domestic Violence Courthouse in Chicago

- California Supreme Court in San Francisco

- Superior Court of California, County of San Francisco

- Federal Courthouse in Miami

- Miami-Dade Family Court

- Edward W. Brooke Courthouse in Boston

- John Adams Courthouse in Boston

The Committee also thanks the following entities for hosting its meetings in San Francisco, Washington, D.C., and Boston: the California Administrative Office of the Courts, the California Judicial Council, the District of Columbia Courts’ Education and Training Division, the Massachusetts Division of Capital Asset Management, the Massachusetts Administrative Office of the Trial Court, and the Boston Society of Architects.

In addition, the Committee appreciates the expertise, information, and guidance provided by various individuals in scheduled presentations and briefings to the Committee, including: Chief Judge Annice M. Wagner of the DC Court of Appeals, Chief Judge Rufus G. King, III, of the Superior Court of D.C., Michael Kazan of Gruzen Samton, Architects, Planners, and Interior Designers LLP; Francis Burton, Coordinator of the Office of Court Interpreting Service for the D.C Superior Court; Beverly Prior, Randy Dahr, Edward Spooner, Charles Drulis, and Frank Greene of the American Institute of Architects’ Academy of Architecture for Justice; Mary Lamielle of the National Center for Environmental Health Strategies, Inc.; Susan Molloy of the National Coalition for the Chemically Injured; Professor Rebecca Morgan, Dr. Karen Griffin, Dan Payne, and Professor Roberta Flowers of Stetson University; Danielle Strickman of the Disability Independence Group; Daniel Holder of the Miami-Dade County Office of ADA Coordination; Chief Justice Robert A. Mulligan of the Massachusetts Administrative Office of the Trial Court; and David Perini, Liz Minnis, and Polly Welch of the Massachusetts Division of Capital Asset Management.

Members of the Courthouse Access Advisory Committee

- Accessibility Equipment Manufacturers Association, Gregory L. Harmon

- Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts, Gate Lew, AIA

- American Institute of Architects, James L. Beight, AIA and Andrew Goldberg, Assoc. AIA

- American Bar Association, Honorable Norma L. Shapiro

- Arizona State Bar Association, James B. Reed

- California Administrative Office of the Courts, Honorable Frederick P. Horn, Gordon “Sam” Overton, and Linda McCulloh

- Conference of State Court Administrators, Steven C. Hollon and James T. Glessner

- Cook County (IL) Government, Warrick Graham, AIA

- David Calvert, PA

- Disability Rights Legal Center, Eve L. Hill and Paula Pearlman

- District of Columbia Courts, H. Clifton Grandy

- Disabilities Law Project, Rocco J. Iacullo

- Hearing Loss Association of America, Marcia Finisdore and Diana Bender

- HDR Architecture, Inc., Luis F. Pitarque, RA

- Hellmuth, Obata and Kassabaum, Inc., Robert W. Schwartz, AIA

- International Code Council, Kimberly Paarlberg, RA and Phil Hahn

- Lift-U Division, Hogan Manufacturing, Don W. Birdsall

- Michael Graves & Associates, Thomas P. Rowe, AIA and Michael A. Crackel, AIA

- Michigan Commission for the Blind, Patrick D. Cannon

- Montana Advocacy Program, Philip A. Hohenlohe

- National Association for Court Management, Roy S. Wynn, Jr.

- National Center for State Courts, Chang-Ming Yeh

- National Fire Protection Association, Nancy McNabb, AIA and John C. Biechman

- New Hampshire Governor’s Commission on Disability, Cheryl L. Killam

- Ninth Circuit for the U.S. Courts, Honorable Michael R. Hogan

- Paralyzed Veterans of America, Maureen McCloskey and Mark Lichter, AIA

- PSA-Dewberry, Inc., Marlene Shade, AIA

- Steven Winter Associates, Inc., Stephanie Vierra

- Superior Court of the District of Columbia, Honorable Patricia A. Broderick

- T.L. Shield & Associates, Tom Shield

- Tenth Judicial Circuit Court of Florida, Honorable Susan W. Roberts and Nick Sudzina

- U.S. Department of Justice, Janet L. Blizard and Tracy Justesen

- U.S. General Services Administration, Robert L. Andrukonis, AIA and Thomas Williams, AIA

- U.S. Judicial Conference, Securities and Facilities Committee, Honorable Joseph F. Bataillon

- United Spinal Association, Kleo J. King

Also active in the work of the Committee were:

- Bob Gammon, American Disabilities Consultants

- Nina Gladstone, Spillis Candela DMJM

- Katherine McGuinness, Kessler McGuinness & Associates, LLC

Access Board Representatives and Staff

- Denis Pratt, AIA, Board Member

- Elizabeth Stewart, DFO/ Board Member

- Dave Yanchulis, Staff Member/ DFO

- Earlene Sesker, Staff Member

- Meriel Brooks, Staff Member

- Rose Bunales, Staff Member

- Tanya Johnston, Staff Member

I. Introduction

The design of courthouses poses challenges to access due to unique features, such as courtroom areas that are elevated within confined spaces. Determining the best way to provide access to these spaces can be difficult. While the U.S. Access Board has established guidelines for courthouses which cover access to courtrooms, many have sought guidance on how access can best be achieved. Additional information is needed that explores new or innovative design solutions. In October, 2004, the U.S. Access Board organized an advisory committee to develop such guidance and to promote access to courthouses as part of an overall plan for targeted outreach on different aspects or spheres of accessibility.

The Courthouse Access Advisory Committee’s (CAAC) 35 members included designers and architects, disability groups, attorneys, members of the judiciary, court administrators, representatives of the codes community and standard-setting entities, government agencies, and other volunteers with an interest in the issues to be explored. The members were selected among applications the Board received in response to a published notice. The Committee was charged with developing design solutions and best practice recommendations for accessible courthouses. In addition, the Committee’s charter called for recommendations on outreach and educational strategies for disseminating this information most effectively to various audiences.

Over the course of its two-year charter, the Committee met quarterly in different cities and toured various types of courthouses in each location. Committee meetings were held in Phoenix, Chicago, San Francisco, Miami, Boston, and Washington, D.C. In developing its recommendations, the Committee followed a consensus-based model according to protocols governing Federal advisory committees. Three Subcommittees organized by the Committee covering court suites, courthouse spaces other than courtrooms, and education and outreach met extensively in between committee meetings.

As a result of this process, the CAAC was able to more closely examine and understand regional differences and approaches to courthouse access issues, as well as differences between local, state, and federal court systems. This led to more effective communication among a larger group of individuals who serve and contribute to the courts systems. The most significant lesson the CAAC learned from its investigation is that the most accessible designs arose in court systems that considered access at the outset of the project and involved people with disabilities at that point. Additionally, whenever flexibility was built into the courthouse, courtrooms, and services, it was easier to accommodate and/or provide the required or requested services for people with disabilities. Architectural elements of the courthouse and courtrooms only go so far in supporting the larger picture of courthouse access. So it was determined that addressing program services and promoting better communication and education among the judicial associations were critical components to effectively solving access issues. The final CAAC documents have been developed with a cross-disciplinary focus and are intended to support and communicate an integrated process as the way to address and resolve courthouse access issues for the most successful outcome.

This document is comprised of the reports from each Subcommittee as adopted by the Committee.

Courthouse Design

The report’s recommendations cover access to areas and elements of courthouses other than courtrooms, including building entrances, interior and exterior routes, egress, signage and wayfinding, jury assembly areas, clerks’ offices, and conference rooms. This information clarifies how existing guidelines can be met and includes best practice recommendations for optimum accessibility. It also identifies common access problems and details effective design solutions.

Court Suite Design

Best practice recommendations and their related spaces, including judges chambers, jury deliberation suites and in-custody defendant holding. Design solutions addressed in the report cover access to courtrooms. Elements particular to courtrooms included entrances, witness stands, jury boxes, judges’ benches, clerk’s stations and other work stations, and assistive listening systems, among others. Guidance is provided on how to achieve access most effectively while preserving traditional and necessary features of courtroom design. Recommendations also address associated spaces, including jury deliberation rooms, holding cells, and judges’ chambers.

Education and Outreach

The report provides recommendations for outreach, marketing, and partnership strategies to promote accessibility to courthouses and to disseminate the Committee’s design guidance among target audiences, including design professionals, judicial officers, court managers, court staff, and disability groups. The Committee recommends that a website be the main avenue for disseminating this information, and its report provides recommendations for the structure, content, and marketing of such a website. The report contains suggestions for tailoring website material to various audiences and provides narrative content for web pages. Recommendations also address training courses for architects and designers and for judges and court administrators.

II. Recommendations for Accessible Courthouse Design

- Exterior Route

- Courthouse Entrance

- Interior Accessible Route, Protruding Objects, and Signage

- Accessible Means of Egress

- Specific Function Areas

Exterior Route

The site arrival point must be as close as possible to an accessible entrance while allowing for security measures. The exterior route should provide a safe and integrated way for people with disabilities to access the courthouse.

Passenger Loading Zone/Drop-off Area

Minimum Requirements:

Where a passenger loading/drop-off zone is provided, an access aisle that is 60 inches wide and the same length of the vehicle pull-up space must be provided adjacent and parallel to the zone.

If a valet parking service is provided, there must also be an accessible passenger loading zone.

Figures: Drop off areas that provide clear and level entry.

Recommendations for Best Practice:

- Though not required by regulations, a passenger drop-off area is often needed for individuals with mobility impairments who may find travel distances from parking areas excessive.

- Where practical, and in climates with inclement weather, it is desirable to provide overhead protection from the curb to the entry.

Commentary:

- There are often both public drop-off passenger loading zones (drop-off areas) and secured drop-off (“sally ports”) elements. Some courthouses, such as those for family court, also may require a separate witness or victim drop-off area and travel route.

- All passenger loading zones are required to be accessible. It is common to assume that prisoners with disabilities do not need a barrier-free path because they are always under guard supervision. However, prisoners need to be afforded the same mobility independence whether or not they have a disability.

Applicable Guidelines:

Scoping:

209 or F209 Passenger Loading Zones and Bus Stops

Technical:

503 Passenger Loading Zones

Parking

Figure: Accessible parking spaces close to building entry.

Minimum Requirements:

Accessible parking spaces are required based on the total number of parking spaces provided in each lot. Adjacent and parallel access aisles are also required. When multiple accessible entrances are provided, accessible parking must be dispersed at each accessible entrance. Accessible parking spaces must be located on the shortest accessible route from the parking lot to an accessible entrance.

Recommendations for Best Practice:

- Due to security concerns and site conditions, especially in urban environments, parking areas are often located remotely from the courthouses they serve. Distance, traffic, curbs, and other barriers make this problematic for many people with disabilities. Every effort should be made to mitigate these issues so that the accessible parking spaces can be located as close as possible to each type of entrance.

- Accessible routes serving parking space spaces should be configured to avoid travel behind other spaces and parked vehicles.

- Access aisles must be marked in a way that discourages parking within them. Post a “No-Parking” sign for each access aisle or place a bollard at the traffic side of the access aisle to prevent people from parking in the access aisles.

Commentary:

Often there are public parking lots, employee parking lots, and restricted parking lots, all of which require accessible parking spaces.

Common Errors:

- Restricted and employee parking lots do not provide the minimum number of accessible spaces or an accessible route from parking to building entrances.

- Multiple parking facilities where all accessible parking is provided in only one area. It is important to distribute accessible parking at each accessible entrance.

- Accessible spaces that do not have access aisles.

- Built-up curb ramps that protrude into access aisles.

- No safe accessible route from accessible parking spaces.

Applicable Guidelines:

Scoping:

208 or F208 Parking Spaces

Technical:

502 Parking Spaces

Site Arrival Points and Entrance Approach

Minimum Requirements:

At least one accessible route must be provided within the site from accessible parking spaces and accessible passenger loading zones, public streets and sidewalks, and public transportation stops, to the accessible entrance(s) of the courthouse.

The exterior accessible route must be at least 36 inches wide, no steeper than a grade of 1:20 (for a ramp, a maximum grade of 1:12) and have a surface that is stable, firm, and slip resistant, in addition to meeting other specifications.

When security barriers are used (bollards, planters, etc.) there must be sufficient space between them for wheelchair clearance.

Recommendations for Best Practice:

- If parking cannot be located adjacent to the courthouse due to site conditions or security concerns, benches and level areas should be provided for visitors who can not ambulate long distances. It is recommended to locate the benches every 200 feet along the path of travel.

- The entry to the courthouse is often raised on a plinth for many reasons, both aesthetic and functional. However, given the impact on people with mobility impairments, the height differential should be minimized and carefully integrated with access requirements. Other design icons can be just as effective without inherently creating access barriers that force people with disabilities into segregated routes.

- If raising the building entrance off grade is necessary, the change in elevation should be as minimal as possible. This will allow shorter routes and, where necessary, shorter ramps with more gradual slopes. Consider eliminating steps, even at raised entrances, so that all public visitors ascend a wide, gradually sloped walkway. It is most equitable if people with and without disabilities use the same path of travel to the courthouse entrance.

- If a ramp is necessary, the slope should be as gradual as possible. The ramp should be wide enough to allow for ambulatory companions, thus exceeding the minimum width of 36 inches between the handrails. To provide integration, the ramp should begin with the general circulation path.

|

Figure: resting area for excessive paths of entry

Figure: Plinth with stairs creating access problems

Commentary:

- The use of a raised plinth as a design element to symbolize power and authority dates back to antiquity. Other designs can just as effectively achieve this symbolism. Security can be addressed by other means, such as bollards, planters, or a deeper building setback from the street with an entry plaza. If a high water table is the concern, this too can be addressed by other means, such as improved site drainage or raising the building only the minimum amount required.

- It is important to consider accessible design when making the decision whether to raise the main entrance above grade. It is preferable to make the main entrance accessible because separate entrances raise security issues and may be discriminatory. People with disabilities equate having to use a separate entrance with not being treated equally.

- Reliance on a mechanized conveyance device, such as a lift or elevator, as the only accessible route into the building can result in a lack of access. The use of lifts is limited in new construction and, in the case of exterior routes, is allowed only where existing exterior site constraints make a ramp infeasible. Elevators and lifts are often out of service due to scheduled maintenance and malfunctions (especially common at exterior installations). They can also be unsightly. Locked lifts are not permitted by the guidelines. If security or vandalism is a concern, it must be addressed in a way that does not inhibit independent use by people with disabilities.

Figure: Courthouse without plinth for easier access.

Common Errors:

- Sloped surfaces that are too steep or exceed cross slope limitations.

- No accessible route from public transportation stops to the courthouse.

- Use of lifts as part of an accessible route where ramps are feasible.

- Changes in elevation that result in long, circuitous and arduous ramps.

Figure: Plinth necessitates a ramp that is long and arduous

Applicable Guidelines:

Scoping:

206 or F206 Accessible Routes

Technical:

Chapter 4 Accessible Routes

Courthouse Entrance

Courthouse entrances often serve different groups of users. Public entrances are used by spectators, visitors, witnesses, jury pool, attorneys, public safety officers, victim and witness advocates, and court employees. Restricted entrances are used by judges, jurors, public safety officers, victims, and court employees. Detainees enter the courthouse only via secure entrances. It is important that access is provided for each type of entrance, including public, restricted, and secure entrances.

Minimum Requirements:

In new construction, the guidelines require that, at a minimum, the following entrances be accessible:

- At least 60% of public entrances must be accessible. Public entrances are those entrances that are not a service entrance or a restricted entrance.

- All entrances from parking garages that provide direct pedestrian access between the garage and the building or facility.

- At least one entrance from each tunnel or elevated walkway that provides direct pedestrian access.

- At least one restricted entrance, which is an entrance that is made available for common use on a controlled basis, but not for public use, and that is not a service entrance.

- At least one detainee entrance. Doors operated solely by security personnel are exempt from the specific requirements for hardware, opening force, closing speed, and automation. Only doors operated solely by security personnel qualify for this exemption. Entrance doors operated sometimes by security personnel and sometimes by employees or the public must meet all requirements for accessible entrances.

- At least one entrance to each tenancy in the building or facility.

- At least one service entrance if it is the only entrance to a tenancy.

- At inaccessible entrances, signage is required to direct people to the accessible entrances.

Figure: Inaccessible entrance with signage directing people to an accessible entrance.

Figure: Detainee entrance with ramp.

Many magnetometers cannot accommodate wheelchair traffic. An accessible route adjacent to the magnetometer that is at least 36 inches wide is required where magnetometers are not accessible. The accessible route must be located so that a person with a disability can keep his/her personal belongings within sight.

Where two-way communication systems are provided at entrances, they must be accessible.

- Handsets: Handsets must be located within accessible reach ranges and on a clear, level space preferably out of the swing of the door. The handset cord must be at least 29 inches long so that it reaches to a person in a standing or seated position.

- Audible and Visual Signals: The system must provide both audible and visual signals.

Recommendations for Best Practice:

- All public and employee entrances should be accessible.

- Consider providing adequate space at the building entrance for indoor queuing while waiting for security screening.

- Because people often must interact with security personnel, screening procedures should be posted. This can minimize circumstances when a security guard thinks that a person is ignoring him/her when, in fact, the person has a hearing loss and has simply not heard him/her. A compliant printed or electronic sign summarizing security procedures should be posted in plain view.

- Entrance doors should be provided with an automatic door opener. Where there are separate paths for entry and exit, an automatic door opener should be available at both locations.

- Accessible detainee entrances protect the civil rights of a detainee and reduce the security risk involved with physically assisting detainees with disabilities. Detainees with disabilities should use the same entrance(s) as detainees without disabilities.

- Accessible means of egress requirements may exceed accessible entrance requirements. Refer to the chapter devoted to means of egress for more information.

Figure: Exterior door with power operated

Figure: Exterior door with power operated

door in use.

Commentary:

Courthouse doors are often large and heavy. While there is no minimum force requirement for exterior doors, if the opening force at an entrance door is greater than 5 pounds, automated doors should be provided. (Automated doors or power assisted doors are required for all U.S. General Services Administration buildings under its Public Building Standards.)

Common Errors:

- Not providing an accessible entrance for prisoners with disabilities.

- Failure to provide directional signage to accessible entrances at inaccessible entrances.

- Having a security layout that separates people with disabilities from their belongings without allowing them to maintain visual contact at security entrances.

Applicable Guidelines:

Scoping:

206 or F206 Accessible Routes (including 206.4/ F206.4 Entrances and 206.8/ F206.8 Security Barriers)

216.6 or F216.6 Signs/ Entrances

230 or F230 Two-Way Communication Systems

Technical:

Chapter 4 Accessible Routes

703 Signs (sections 703.5 and 703.7)

708 Two-Way Communication Systems

Interior Accessible Route, Protruding Objects and Signage

Minimum Requirements:

At least one accessible route is required to connect all accessible elements and spaces in the building. Specifications for accessible routes cover doors, clear width, walking surfaces, running and cross slopes, and changes in level. The guidelines require floor surfaces to be firm, stable and slip resistant. With the exception of fire doors, the maximum door opening force is 5 pounds.

Specifications for protruding objects apply on all circulation paths, not just accessible routes. Headroom clearance of at least 80 inches is required along all circulation paths. Where the headroom clearance is less than 80 inches, fixed barriers are required to prevent hazards.

Stairs are not permitted as part of an accessible route. However, stairs that are part of the means of egress must comply with the guidelines for handrails, treads, and risers, regardless of whether there is a ramp or an elevator that connects those levels. Stairs must provide solid risers, minimal nosing projection, and handrails. For all new courthouse buildings with more than one story, elevators are required.

Signs, including information and directional signs, are subject to requirements for finish and contrast, the height, style, spacing, and proportion of characters, and line spacing. Signs labeling permanent rooms and spaces and exit doors are also required to be tactile and have raised and braille characters. Permanent rooms and spaces in a courthouse include, but are not limited to, courtrooms, hearing rooms, judge’s chambers, law libraries, jury assembly rooms, jury deliberation rooms, restrooms and egress stairs.

Where two-way communication systems are provided for entry into a restricted area, they must be accessible.

- Handsets: Handsets must be located within accessible reach ranges and on a clear, level space, preferably out of the swing of the door. The handset cord must be at least 29 inches long so that it reaches to a person in a standing or seated position.

- Audible and Visual Signals: The system must provide both audible and visual signals.

Recommendations for Best Practice:

|

Figure: Building directory that can be read from a wheelchair

- Becaus e many courthouses are large buildings, an informative and user-friendly building directory and/or map at the entrance will provide assistance to the public for finding the rooms they need as well, as the shortest, most accessible route. They can also help identify the availability of accessible elements, such as assistive listening systems and TTY-equipped phones. When provided, a building directory should be mounted at a height that allows both a person who is seated and one who is standing to read it. Three-dimensional or tactile maps help people with vision impairments in finding their way around the building. The directory near the courthouse’s entrance and at other locations throughout the courthouse should be legible with a Sans Serif font that contrasts with its background and is of sufficient size to be easily readable. If an electronic building directory or information kiosk is used, consider including an audio component so that it is usable by people with visual impairments.

- The guidelines require that people with disabilities follow the same route as that of the general public but where the routes must diverge – at stairs, for example - signage clearly identifying the alternate, accessible path of travel should be provided so that no backtracking is necessary. Where the interior accessible route includes an elevator, the elevator should be located within close proximity to, and visible from, the stairs.

- For all doors along accessible routes, consider accessible approaches and clearances from all directions.

It is important to consider the wayfinding needs of people with vision impairments. See Appendix B on Wayfinding. - It is important to consider acoustics in courtrooms and other areas to provide access for people with hearing loss. See Appendix A.

- Courthouses often require people to travel substantial distances between areas. Providing benches, rest areas and railings are recommended to accommodate people with stamina and mobility limitations.

- Limiting distance from primary function areas to restrooms is recommended.

Commentary:

- Although there are many people who cannot climb stairs, many people with disabilities do use stairs. Stairs are often the shortest route between two points and preferred by some people with disabilities, including those who use crutches.

- Courthouse floors are often highly polished, and may become slippery when wet. The floor materials, as well as products used to maintain floors, should be evaluated for their slip resistance.

Common Errors:

- Difficult-to-open heavy ornamental interior doors.

- Customized doors with hardware mounted too high to operate easily.

- Open areas under stairs, especially under the grand staircases in courthouses, that are not protected by railings or other barriers and are thus hazardous to people with vision impairments where the headroom clearance is below 80 inches.

- Wall-mounted objects that project into circulation paths without proper treatment as protruding objects, including counters, water fountains, displays, and exhibits.

- Lack of elevator access to upper levels.

- Stairs with open risers.

- Signage that is not legible.

Applicable Guidelines:

Scoping:

204 or F204 Protruding Objects

206 or F206 Accessible Routes (including 206.4/ F206.4 Entrances and 206.8/ F206.8 Security Barriers)

210 or F210 Stairways

216 or F216 Signs

230 or F230 Two-Way Communication Systems

Technical:

307 Protruding Objects

Chapter 4 Accessible Routes

504 Stairways

703 Signs

708 Two-Way Communication Systems

Accessible Means of Egress

The guidelines provide requirements for notification and evacuation for emergency situations. Accessible means of egress is a three-step process that requires planning, notification, and physical evacuation.

Whether a jurisdiction adopts the International Fire Code or the NFPA 101 Life Safety Code, fire codes require planning for emergency evacuation through Fire and Safety Evacuation Plans. These plans include consideration of the accessible routes and assistance available to persons with physical disabilities.

The guidelines address fire alarm systems and reference technical specifications in the National Fire Alarm Code (NFPA 72). The guidelines also address accessible means of egress through a reference to the International Building Code (IBC).

|

Figure: Audible and visual

fire alarm

Notification

Minimum Requirements:

The guidelines require fire alarm systems to comply with the NFPA 72 (1999 or 2002 editions). However, the guidelines specify a lower sound level maximum (110 instead of 120 decibels).

Audible alarms are required to be heard throughout all occupied spaces in the courthouse, including bathrooms, judicial chambers, and jury areas. Visible alarms are required in all public areas and all common areas, including corridors and restrooms. Visible alarms are not required in employee work areas if the wiring system is designed so that visible alarms can be integrated into the alarm system at a later date as needed.

Recommendations for Best Practice:

- Notification should be rapid and redundant, with alternative systems and strategies for notifying courthouse occupants. These may include: visible and audible fire alarm signals, text messages to pagers, cell phones, and PDAs, public address system announcements, monitors and signs with text messages, instant mail, telephonic public address announcements, and instructions by the security/emergency personnel.

- When designing control panel boards for the fire alarm system, allow a minimum of 20% of the private offices to have visible alarms added later.

Common Errors:

- No consideration for future visible alarm connections.

- Not having audible alarms that can be heard throughout all occupied spaces.

- Not having visible alarms in public and common areas, such as toilet rooms, employee areas, and small conference/waiting areas.

Applicable Guidelines:

Scoping:

215 or F215 Fire Alarm Systems

Technical:

702 Fire Alarm Systems

NFPA 72 National Fire Alarm Code, 1999 or 2002 edition (referenced by 702)

Evacuation

Minimum Requirements:

The guidelines reference the International Building Code (IBC) for accessible means of egress requirements (section 1003.2.13 of the 2000 edition with 2001 Supplement or section 1007 of the 2003 edition).

For buildings and spaces, when one means of egress is required, that means of egress must be accessible. When two or more means of egress are required, at least two must be accessible. IBC requires that any space with 50 or more persons have two means of egress. Signage is required at the elevators and any other inaccessible means of egress directing persons to the locations of the accessible means of egress or area of assisted rescue.

|

Figure: Designated area of refuge

next to elevators

Accessible means of egress include an accessible route either out of the building and to a public street, or to a designated and properly protected area where assistance for evacuation will be provided. This can be an area adjacent to either an elevator with emergency power, or an area adjacent to an exit stairway, where a person with a disability can safely wait for rescue assistance.

Courthouses with an automatic sprinkler system are not required to have areas of refuge. However, this exemption does not mean that accessible routes are not required to areas where assistance will be first available.

At ground level, an accessible route must be provided from the exit door to the public way. If, for some reason, the exterior accessible route is not available (e.g. steep site or retaining walls), an alternative is an exterior area for rescue assistance. This is an exterior area that provides a level of protection similar to what is specified for an interior area of refuge. For specific requirements see IBC 2003 Section 1007.8.

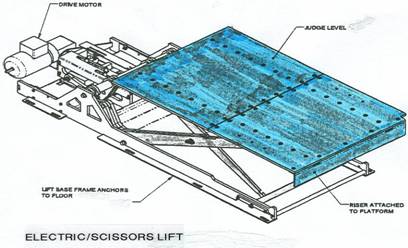

Lifts that are part of an accessible means of egress must have emergency standby power.

Recommendations for Best Practice:

- Special security requirements in courthouses may result in additional requirements for egress. For example, prisoners are often transported from the vehicular sally port or the holding cells to the courtroom on upper levels via an elevator. In an emergency evacuation, the officials responsible for transporting the persons in custody within the courthouse may need emergency power and an elevator control key so that they can override fire department recall and use the elevator for emergency evacuation of prisoners with disabilities.

- Signage should indicate areas where assisted rescue will be provided. Two-way and accessible communication, audible and visible, should be available at the elevator and exit stairways to allow persons to contact the central command center to inform them that they need assistance to evacuate.

- The signage designating emergency egress and non-emergency way-finding should be distinctive and evident in public and nonpublic areas of the courthouse.

Figure: Signage next to elevators with directions for emergency evacuation. Avoid overly complicated signage.

Commentary:

Elevators are not intended for unassisted evacuation. Without knowledge of the location and extent of the emergency, the person could deliver themselves to the fire floor, or suffer smoke inhalation from smoke in the shaft. Assisted rescue should always be with trained personnel.

Common Errors:

- Having a lift without standby power as part of an accessible means of egress.

- No accessible exterior route for exit discharge to a public way.

- Not having signage at the elevators and any non-accessible means of egress identifying the location of the accessible means of egress.

Applicable Guidelines:

Scoping:

207 or F207 Accessible Means of Egress

Technical:

International Building Code, 2000 edition and 2001 supplement, section 1003.2.13 or 2003 edition, section 1007 (referenced by 207/ F207)

Specific Function Areas

Courthouses have many functional areas beyond the courtrooms and chambers that are unique to a courthouse. All of the following areas must comply with the requirements in the guidelines for accessible route, fixed seating, protruding objects, reach range, signage, telephones, work surfaces, and other relevant provisions.

Rooms may be reconfigured for different purposes. A room or space that is intended to be occupied at different times for different purposes must comply with all of the requirements that are applicable to each of the purposes for which the room or space will be occupied.

Public Waiting Areas, Witness Reception/Waiting Areas, Attorney Waiting Areas

Minimum Requirements:

Public waiting areas must be accessible. Access to fixed seating, benches, and visiting areas must be provided.

When provided, separate waiting and reception areas for witnesses and attorneys must be accessible to people with disabilities.

Recommendations for Best Practice:

If portable assistive listening systems are available, provide signage in appropriate locations indicating availability

Commentary:

It is preferred that wheelchair spaces be integrated with fixed seating where provided. Requirements for assembly seating are not intended to be applied.

Common Errors:

- Small rooms that do not allow for wheelchair entrance, maneuvering, and exiting.

- Magazine and literature racks beyond the reach range requirements.

Applicable Guidelines:

Scoping:

206 or F206 Accessible Routes

226 or F226 Dining Surfaces and Work Surfaces

Technical:

Chapter 4 Accessible Routes

902 Dining Surfaces and Work Surfaces

Clerk’s Office and Information Center

Minimum Requirements:

At least one service area of each type of clerk function must be accessible.

A service counter, solely for distribution of information, must provide a height of 36 inches for a width of 36 inches. A counter that is used for completing forms, must provide a height of 28 to 34 inches, along with knee clearance under the surface allowing a forward approach.

The guidelines require that, where counters or service windows have security glazing to separate personnel from the public, a method to facilitate voice communication shall be provided. Where handsets are provided, they must have a volume control.

Recommendations for Best Practice:

- A small audio induction loop system, together with appropriate signage, is helpful for people with hearing loss, even if there is no security glazing.

- Courthouses frequently contain exhibits. These exhibits should be designed to be accessible to people with visual impairments and others with disabilities.

Common Errors:

- Counters that extend more than 4 inches from the wall surface, mounted above 27 inches from the floor, thus becoming protruding objects.

- Counters at heights that obstruct accessibility by being too high, too low, or not allowing for interaction between the customer and staff (e.g. lower ‘accessible’ counter installed below a higher counter or window or flip-up counters).

Applicable Guidelines:

Scoping:

226 or F226 Dining Surfaces and Work Surfaces

227 or F227 Sales and Service

Technical:

902 Dining Surfaces and Work Surfaces

904 Check-Out Aisles and Sales and Service Counters

Central Holding

Minimum Requirements:

A minimum of one of each type cell for adult male/female; juvenile male/female must be accessible.

Refer to Section 14 for additional information on holding cells.

Applicable Guidelines:

Scoping:

231.3 or F231.3 Judicial Facilities/ Holding Cells

231.4 or F231.4 Judicial Facilities/ Visiting Areas

Technical:

807 Holding Cells and Housing Cells (section 807.2)

902 Dining Surfaces and Work Surfaces

904.4 Sales and Service Counters

Attorney/Detainee Interview Room

Minimum Requirements:

5%, but a minimum of one, of interview stations must be accessible on both the attorney and the detainee side of the secure barrier.

The guidelines require that, where counters or windows have security glazing to separate detainees from visitors or attorneys, a method to facilitate voice communication shall be provided. If handsets are provided as a means of communication, they must comply with the guidelines.

Common Errors:

- Not providing access for the detainee with a disability.

- Fixed seating that obstructs wheelchair space.

Applicable Guidelines:

Scoping:

231.4 or F231.4 Judicial Facilities/ Visiting Areas

Technical:

902 Dining Surfaces and Work Surfaces

904.4 Sales and Service Counters

Jury Assembly Area

Minimum Requirements:

All jury assembly and waiting areas must be accessible. This includes kitchens, toilet rooms, and quiet rooms. At least 5% of fixed work surfaces and associated electrical outlets need to be accessible.

Service counters and work surfaces at jury check-in areas must meet the requirements for accessibility.

Assistive listening systems are required in jury assembly areas where audio amplification is used. Assistive listening systems must meet certain technical standards of the guidelines. Identify the availability of assistive listening systems by posting signs with the international symbol for access for hearing loss. A portion of system receivers must be hearing aid compatible. A permanently installed audio induction loop system is an inexpensive solution for this situation.

Figure: Jury Assembly room with power opening door and

signage indicating availability of assistive listening systems.

Common Errors:

- Service counters and work surfaces are too high.

- Lack of signage for the availability of assistive listening systems.

- No assistive listening systems are available.

Applicable Guidelines:

Scoping:

219 or F219 Assistive Listening Systems

221 or F221 Assembly Areas

226 or F226 Dining Surfaces and Work Surfaces

227 or F227 Sales and Service

228 or F228 Depositories, Vending Machines, Change Machines, Mail Boxes, and Fuel DispensersTechnical:

309 Operable Parts (referenced by 228/ F228 for vending machines)

706 Assistive Listening Systems

802 Wheelchair Spaces, Companion Seats, and Designated Aisle Seats

902 Dining Surfaces and Work Surfaces

904 Check-Out Aisles and Sales and Service Counters

Conference Room (Judge’s, Attorney, Witness, etc.)

Minimum Requirements:

All conference rooms must be accessible, including an accessible route to all fixed elements. Sufficient clearances must allow for access into the room and exiting. If provided, surfaces of fixed tables must be between 28 and 34 inches above finished floor and must have a minimum of 27 inches of vertical knee clearance under the table and provide an accessible route to the table and other elements in the rooms.

Recommendations for Best Practice:

There should be sufficient clearance provided so that a person using a wheelchair can get to all amenities within the room when people are seated.

Commentary:

In order to provide people with disabilities full integration in the waiting room, the room should be fully accessible. People who use wheelchairs should have ample room to maneuver around the room.

Common Errors:

One of the most common problems is the lack of adequate clearance in the room or an accessible route through the room.

Applicable Guidelines:

Scoping:

206 or F206 Accessible Routes

226 or F226 Dining Surfaces and Work Surfaces

Technical:

Chapter 4 Accessible Routes

902 Dining Surfaces and Work Surfaces

Grand Jury Suite

A grand jury courtroom may have a variety of configurations. Alternatives extend from a space similar to a conference room, to a typical courtroom setting, and any combination in between. The accessibility requirements for a space would depend on which type of space the grand jury courtroom most closely resembled.

Minimum Requirements:

Access requirements for a grand jury hearing room are identical to that of a courtroom. Counsel table, podium, witness stand, lectern and stadium seating must be accessible. Dedicated toilet rooms and deliberation rooms serving these grand jury areas must provide access to persons with disabilities. (See Part III: Recommendations for Accessible Courtroom Design.)

III. Recommendations for Accessible Court Suite Design

- Courtroom Entry

- Main Aisle

- Accessible Route

- Spectator (Gallery) Seating

- Rail (Bar)

- Jury Box

- Witness Stand

- Judge’s Bench

- Clerk’s and Bailiff’s Stations

- Court Reporter

- Furnishings

- Judges’ Chambers

- Jury Deliberation Suite

- Holding Cells

- Assistive Listening Systems in Courtrooms

Courtroom Entry

Minimum Requirements:

Doors must require no more than 5 pounds of force to push or pull open. Doors must provide at least 32 inches of clear opening width. Maneuvering clearances on the latch and pull side must be provided. Vision panels, accessible door hardware, and kick plates must be provided. For double doors, at least one door must meet the requirements. Doors in series must also provide space between the doors for maneuvering. Vision panels, where provided, must be accessible with a bottom edge 43 inches maximum above the finished floor.

|

Figure: Automatic door operator with

controls located outside door swing.

Recommendations for Best Practice:

The main doors leading into courtrooms should be power operated. The operating pad for power doors must be located outside the swing of the door.

Commentary:

The decision to use heavy, large, or ornate doors leading into a courtroom can make the 5 pound force requirement difficult to achieve and maintain. Even doors that meet the 5 pound force requirement are difficult for many people with disabilities to independently open. Providing power operated doors allows persons with restricted hand strength/mobility to independently open doors.

Common Error:

Doors leading into courtrooms are often ornate and heavy, failing to comply with the 5 pound maximum force to open the door. The 5 pound force limitation is also often not maintained.

Applicable Guidelines:

Scoping:

206.5 or F206.5 Accessible Routes/ Doors, Doorways, and Gates

Technical:

404 Doors, Doorways, and Gates

Main Aisle

Minimum Requirements:

The main aisle must be at least 36 inches wide and the surface of the floor must be level, firm and slip resistant. Carpeting must be securely attached and have a firm cushion, pad, or backing, or no cushion or pad. The pile height is limited to ½ inch maximum.

Recommendations for Best Practice:

The main aisle should be at least 44 inches wide.

Figure: Main aisle in courtroom of adequate width and rail without gate.

Commentary:

Because the main aisle of the courtroom is subject to heavy traffic and wheelchair users must turn into the row to reach the wheelchair seating locations, the main aisle should be a minimum of 44 inches wide.

Common Error:

When carpet is provided, it often has a thick pile or padding, making it difficult for a person using a wheelchair to move.

Applicable Guidelines:

Scoping:

206 or F206 Accessible Routes

Technical:

Chapter 4 Accessible Routes

Accessible Route

Minimum Requirements:

An accessible route is required throughout the courtroom, including from the jury box to the jury deliberation room, from the judge’s bench to chambers, and from the holding area to the defendant’s table, and any other routes intended for users of the courtroom. The route must be at least 36 inches wide, provide a running slope of no more than 1:20 (unless a ramp is provided) and a cross slope of no more than 1:48. Elements in the courtroom must have sufficient clear floor space, minimum 30 x 48 inches, and maneuvering clearances for people who use wheelchairs. Doors along the accessible route must be accessible and meet specifications for hardware, clear width, opening force, and maneuvering clearances, among others.

Doors operated by security personnel only, such as the door from the holding area to the courtroom, are exempt from the requirements for door and gate hardware, closing speed, and opening force.

Recommendations for Best Practice:

Courtroom users with disabilities should be able to use the same approach and participate from the same position as all participants when using public seating, litigants’ tables, jury box, witness stand and lectern.

Commentary:

Segregated or “special” routes for people with disabilities to courtroom elements often cause delays in court proceedings and embarrassment for court users.

Applicable Guidelines:

Scoping:

206 or F206 Accessible Routes

Technical:

Chapter 4 Accessible Routes

Spectator Seating

Minimum Requirements:

Wheelchair spaces are required in assembly areas based on the fixed seating capacity. For example, at least one wheelchair space is required in assembly areas with up to 25 seats, and at least two are required in those with 26 to 50 seats. Wheelchair seating locations must adjoin an accessible route. The wheelchair seating location must not overlap the main aisle.

Wheelchair seating must be at least 36 inches wide and 48 inches deep if a front approach is provided or 60 inches deep if a side approach is provided. Wheelchair seating spaces must provide a level surface and be adjacent to a companion so that the person using a wheelchair is provided shoulder alignment with the person in the adjacent seat.

Where armrests are provided on seats, 5% of the aisle seats must have folding or retracting armrests. If the seats are benches, end caps may remain.

Recommendations for Best Practice:

- Where more than one wheelchair space is provided, wheelchair seating locations should be dispersed, so that individuals using wheelchairs have the same sight lines and variety of choices as other spectators.

- Wheelchair seating locations can overlap the pathway between rows. However, spaces should be designed so that an individual using a wheelchair does not have to move out of the row to allow others to access the row.

Figure: Wheelchair seating locations demonstrating

shoulder alignment with companion.

Figure: Drawing illustrating shoulder alignment for side approach

wheelchair seating spaces.

Commentary:

Wheelchair spaces should be placed so that they are easy to maneuver into and do not obstruct the main aisle or access to seating for other spectators.

Common Error:

Wheelchair seating locations without shoulder alignment with the companion seats, which particularly occurs when pews are located against the back wall.

Applicable Guidelines:

Scoping:

221 or F221 Assembly Areas

Technical:

802 Wheelchair Spaces, Companion Seats, and Designated Aisle Seats

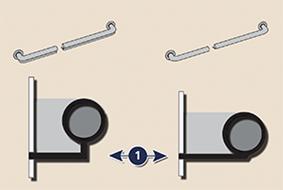

Rail (Bar)

Minimum Requirements:

If a rail is used, the gate or opening in the rail must be a minimum of 32 inches clear width and meet maneuvering clearances. If a gate is provided, at least one leaf must comply. In addition, gates must have compliant hardware and meet specifications for opening force (5 pounds of force maximum), closing speed, and surfacing. The lower portion of gates (within 10 inches above the floor) on the push side must be smooth the full width.

Recommendations for Best Practice:

- If a rail is used, there should be no gate.

- If a gate is provided, it should extend to the floor so a person using a wheelchair can push the gate open with footrests.

Figure: Rail without gate.

Commentary:

Gates can be problematic for people who use wheelchairs and other mobility aids. Swinging gates often hit people as they pass through the opening. If a gate is provided, it should have one leaf. It should not have a double acting spring closure, latches, or other operating mechanisms.

Common Error:

Rails with gates often have spring closures which cause the gate to hit people using wheelchairs while passing through the opening.

Applicable Guidelines:

Scoping:

206.5 or F206.5 Accessible Routes/ Doors, Doorways, and Gates

Technical:

404 Doors, Doorways, and Gates

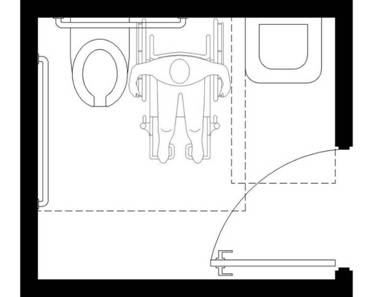

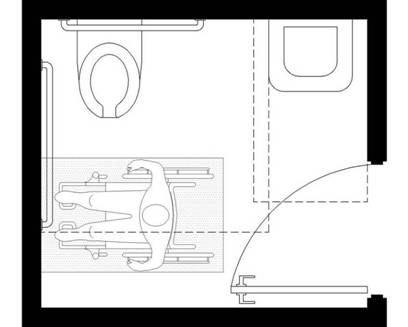

Jury Box

Minimum Requirements:

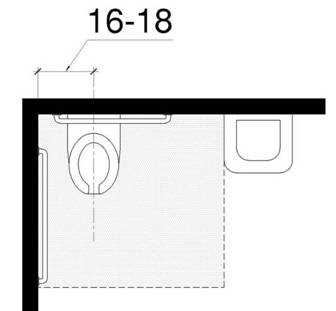

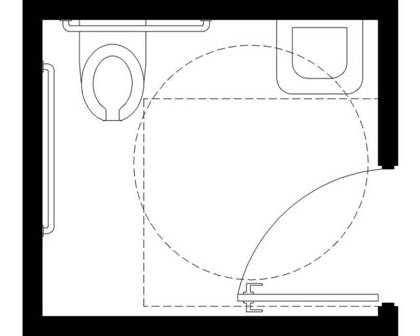

Each jury box must have, within its defined area, wheelchair space that is connected by an accessible route. In general, clear floor space for wheelchairs must be at least 30 inches wide and at least 48 inches deep. Additional maneuvering room is required where the space is confined on three sides by fixed elements such as walls, elevations, railings, or seating. Space entered from the front or back that is confined on both sides more than 2 feet horizontally must be at least 36 inches wide. Space entered from the side that is confined at the front and back more than 15 inches horizontally must be at least 60 inches deep to permit adequate maneuvering space for a parallel approach. The design needs to provide sufficient clear floor space for the person using a wheelchair to get into the space provided,

Recommendations for Best Practice:

- Gates into jury boxes should be avoided.

- Removable seats in wheelchair seating spaces in jury boxes should be readily removable, without requiring tools.

- Jury boxes should be designed for shoulder alignment so a juror with a disability is fully integrated with other jurors.

Figure: Jury Box with first tier on floor.

Option 1: First Tier on Floor (Accessible Pull-In Accommodation)

This design option provides the first row of seating at the same elevation as the courtroom well. It requires a greater depth of distance than standard from the front rail to the chairs to accommodate the required wheelchair maneuvering space. No ramps are needed. Placing a removable seat in the wheelchair space at one end of the first row is minimally obtrusive. The impact upon sight lines should be considered when placing the first row of the jury box at floor level. This scheme appears to be the most cost effective and accessible.

When placing the first row of the jury box at the same level as the well, lines of sight over the courtroom rail should be addressed.

Figure: Floor Plan example of first tier on floor

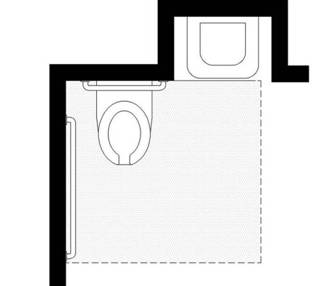

Option 2: First Tier Raised (Accessible Pull-In Accommodation)

This design option provides a raised floor in the entire area between the witness box and the jury box, with a ramp to that floor elevation. A removable chair is provided when the wheelchair space is not needed.

This option depends on a major floor area being raised; and will also require accommodation of the height differential between the courtroom and the access corridor directly adjacent to the courtroom.

Figure: Floor plan example of first tier raised

(Accessible Pull-In Accommodation)

Commentary:

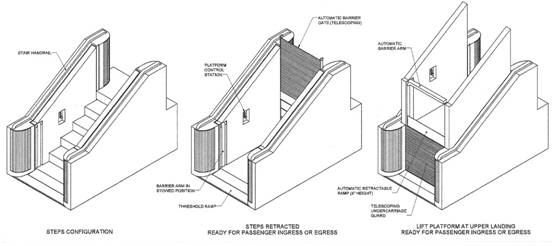

A juror with a disability must be able to enter and exit the jury box without assistance. Lifts may provide a solution in existing facilities, but should be avoided in new construction. Requiring a juror who uses a wheelchair to back into the jury box is also not recommended because people with disabilities should be able to enter the jury box in the same manner as jurors without disabilities. Backing into such spaces can be awkward and time-consuming.

Common Errors:

Gates in jury boxes tend to be heavy because of the millwork and do not allow for unassisted entrance.

Removable seats are often bolted to the floor and require elaborate tools to be removed.

Moveable or flip-down ramps into jury boxes.

Locating wheelchair space outside jury box.

Applicable Guidelines:

Scoping:

206 or F206 Accessible Routes (including 206.7.4/ F206.7.4 concerning the use of platform lifts)

231.2 or F231.2 Judicial Facilities/ Courtrooms

Technical:

Chapter 4 Accessible Routes

808 Courtrooms (sections 808.2 and 808.3)

Witness Stand

Minimum Requirements:

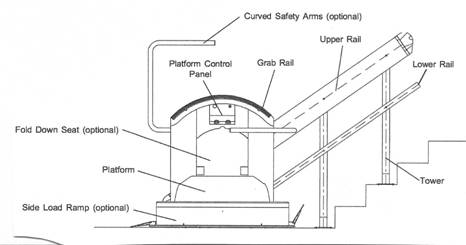

The witness stand must be on an accessible route. If the witness stand is raised, either a ramp or a platform lift may be used to provide access. If a lift is used, it shall provide unassisted entry, operation, and exit. The witness stand shall provide sufficient clear floor space to accommodate a witness who uses a wheelchair. The witness chair shall be easily removable.

Recommendations for Best Practice:

- The witness stand can be anywhere from floor level to one level down from the judge’s bench. The actual height and location should provide direct visual observation of the witness from the judge’s bench, jury box, attorney tables and other locations within the courtroom. For security, the judge and witness should not share the same path into and out of their respective stations.

- If the witness stand is raised above the well, the selection of a ramp or lift should be determined by available space and visual impact on court decorum. Ramps are preferable to lifts for a number of reasons (See Access to Raised Elements).

- If a ramp is selected, it must be permanently installed. The ramp should not interfere with or restrict movement throughout the courtroom. Ideally, one ramp should serve both the witness stand and the jury box.

Figure: Floor plan example of ramp serving both jury box and witness stand.

- When a lift is used, it should be integrated into the witness stand so the lift function is only evident when the lift is in use. Access should not require assistance from anyone outside the courtroom or require special training to operate the lift. The lift should operate without the need for a key. Court staff should have access to lift controls to assist a person unable to operate the lift.

Figure: Witness stand at floor level.

Figure: Ramp access to witness stand.

Commentary:

When locating the witness stand, the design decision should recognize that ability to view the witness’s composure and deportment is of paramount importance to the judge and jury. Maintaining the sight lines necessary to view the witness’s face and body language is imperative.

If the design requires elevating the witness stand, either a lift or ramp may be used to provide access. The best use of space and protection of courtroom decorum should be considerations in the design decision. If a lift is chosen, it should be concealed within the witness stand design so that the lift function is not readily apparent unless the lift is in use. The lift should operate quietly and should not draw attention to the user.

Too often, access to the witness stand is considered at the end of the design process and then compromises and concessions to the design must be made. Sight lines are compromised and ramps are installed in a way that impedes normal traffic and flow about the courtroom.

Having equipment like a lift behind the witness, rather than concealed in the millwork, detracts from the courtroom decorum and aesthetics.

Common Errors:

- Insufficient space to permit a person using a wheelchair to move into and out of the witness stand.

- Fixed chairs cannot be removed without outside assistance.

- Lifts that are not independently operable.

Applicable Guidelines:

Scoping:

206 or F206 Accessible Routes (including 206.7.4/ F206.7.4 concerning the use of platform lifts)

231.2 or F231.2 Judicial Facilities/ Courtrooms

Technical:

Chapter 4 Accessible Routes

808 Courtrooms (sections 808.2 and 808.3)

Judge’s Bench

Minimum Requirements:

The route from the judge’s chamber to the bench must be accessible. The bench platform is typically elevated above the courtroom well and often above the floor level of the judge’s chamber. Vertical access to the bench may be accessible or adaptable. Access to the bench platform to overcome a vertical offset can be achieved by either a ramp or lift. If a lift is used, it must provide unassisted entry, operation, and exit. If adaptable, provision for utilities and space for future accessibility must be included in the design. Adequate space for a future ramp or lift must be provided, including, in the case of lifts, power and a pit, if required.

The bench platform, if served by a ramp or a lift with an entry ramp, must provide wheelchair turning space. If necessary, part of the turning space can be under fixed desk surfaces, if adequate knee and toe clearances are provided. The work surface height must be between 28-34 inches.

Recommendations for Best Practice:

- Historically, the judge’s bench is the highest elevation in the courtroom. If the bench is raised, it should be 6 – 7 inches above the next lower level so that lines of sight to the jury box, witness stand, and court reporter are maintained.

- Ramps are preferable to lifts for access to the judge’s bench for a variety of reasons (See Access to Raised Elements).

- While all benches are permitted to be adaptable, it is preferable to make benches in all courtrooms fully accessible. This limits the need for more expensive alterations when accessibility is required later. In the alternative, the bench in at least one courtroom of each type should be fully accessible by a ramp or platform lift installed at the time of initial construction in order to facilitate situations where an immediate need for accessibility arises.

- To assure proper decorum and security, access to the judge’s bench, whether by ramp or lift, should be out of sight of the courtroom and independently operable. The judge should enter the courtroom at the judge’s bench level. If an adaptable route, rather than a fully accessible route to the bench is provided, as is permitted by the guidelines, select a specific ramp or lift, complete the design and either install it at the time of construction or at a later date.

- The judge should be able to enter and exit the bench moving forward and should have enough room to maneuver freely to hold sidebar conversations and to communicate with other court personnel. Adjustable height work surfaces should be provided when practicable.

- When it is not possible to provide access for a lawyer with a disability to have a face-to-face conversation with the judge, audio technology should be employed to provide confidential conversation between the judge, lawyer, court reporter, and other staff. “White noise” or other sound control should be used so the conversation can be heard by the participants only.

Figure: Judge’s bench in a new courtroom with a ramp.

Commentary:

The judge’s position of authority and personal security is protected by having the judge arrive or depart the judge’s bench level without being visible to the courtroom. By positioning the ramp or lift to the judge’s bench outside the courtroom, no valuable courtroom space is consumed by the ramp or lift. For security, the judge and witness should not share the same path into and out of their respective stations.

Common Errors:

- Often, courtrooms are designed in a way that compels judges who use wheelchairs to access the bench in plain sight of the courtroom. This can call unnecessary attention to the judge’s disability, disrupt the courtroom and undermine the judge’s authority.

- Benches that are too high cause the judge’s view to be blocked or require excessive maneuvering to interact with lawyers or court personnel who need to communicate with the judge from the well of the court.

- Designs fail to consider accessibility, making later modification unnecessarily expensive. Failure to provide adequate space on the bench requires a judge with a disability to make numerous unnecessary maneuvers. Lack of space also prevents judges from being able to move freely to hold sidebar conferences. Additional time and effort is then required to compensate for the lack of accessibility for both the judge and the lawyers.

Applicable Guidelines:

Scoping:

206 or F206 Accessible Routes (including 206.2.4/ F206.2.4, Exception 1 concerning adaptability and 206.7.4/ F206.7.4 concerning the use of platform lifts)

231.2 or F231.2 Judicial Facilities/ Courtrooms

Technical:

Chapter 4 Accessible Routes

808 Courtrooms (sections 808.2 and 808.4)

902 Dining Surfaces and Work Surfaces

Clerk’s and Bailiff’s Stations

Minimum Requirements:

The route to the clerk’s and bailiff’s stations must be accessible. The station platform is typically elevated above the courtroom well and often above the floor level of the secured corridor. Vertical access to a raised station may be accessible or adaptable. Access to the station platform to overcome a vertical offset can be achieved by either a ramp or lift. If a lift is used, it must provide unassisted entry, operation, and exit. If adaptable, provision for utilities and space for future accessibility must be included in the design.

Where raised, stations served by ramps or lifts with entry ramps must have wheelchair turning space. If necessary, part of the turning space can be under fixed desk surfaces, if adequate knee and toe clearances are provided. The work surface height must be between 28-34 inches.

Bailiffs’ duties differ by jurisdiction. Sometimes they are aides to the judge, while other times they act as marshals. If a bailiff’s station is built into the courtroom design, it must comply with the ADA/ABA Guidelines. Its location and requirements should be determined by the duties that the bailiff is expected to perform.

Recommendation for Best Practice:

- Provide an accessible/adaptable path to both the private circulation corridor and the courtroom well. If the route is adaptable, leave space for future lift or ramp including power to both locations. Select a specific ramp or lift, complete the design and either install at the time of construction or at a later date. Ramps are preferable to lifts for access to the clerk’s and bailiff’s stations for a variety of reasons (See Access to Raised Elements).

- The clerk’s station should be designed to enable the clerk to enter and exit the bench moving forward and to move freely to interact with the judge, courtroom personnel, lawyers or witnesses when handling evidence and exchanging documents. When located next to the judge, the clerk’s station should be no more than two steps below the bench for ease of communication and passage of materials between the clerk and the judge.

|

Figure: Clerk’s station level with well

Commentary:

Because the clerk must interact with all participants in the courtroom, it is important that an accessible route connect the clerk’s station with the well, jury box, witness stand and other elements of the courtroom.

Common Errors:

Current courtroom design often fails to consider accessibility for court personnel.

The clerk is stationed so far below the judge that interaction is impeded.

No accessible route is provided between the clerk’s station and the well of the courtroom.

Applicable Guidelines:

Scoping:

206 or F206 Accessible Routes (including 206.2.4/ F206.2.4, Exception 1 concerning adaptability and 206.7.4/ F206.7.4 concerning the use of platform lifts)

231.2 or F231.2 Judicial Facilities/ Courtrooms

Technical:

Chapter 4 Accessible Routes

808 Courtrooms (sections 808.2 and 808.4)

902 Dining Surfaces and Work Surfaces

Court Reporter Station

Minimum Requirements:

The route to court reporter stations must be accessible. The station platform is sometimes elevated above the courtroom well and/or above the floor level of the secured corridor. Vertical access to a raised employee station may be accessible or adaptable. Access to the station platform to overcome a vertical offset can be achieved by either a ramp or lift. If a lift is used, it must provide unassisted entry, operation, and exit. If adaptable, provision for utilities and space for future accessibility must be included in the design.

|

Figure: Court reporter’s station level with well

Figure: Court reporter’s station level with well

Raised stations served by ramps or lifts with entry ramps must provide wheelchair turning space. If necessary, part of the turning space can be under fixed desk surfaces, if adequate knee and toe clearances are provided. The work surface height must be between 28-34 inches.

Recommendations for Best Practice:

- Court reporters’ stations are generally located in front of the bench or between the judge and the witness. If the court reporter station is located between the judge’s bench and the witness stand, the workspace should be built in and care must be taken to make sure the reporter does not block the judge’s view of the witness.

- The design should provide an accessible route between the reporter’s normal location to the sidebar area, to the judge’s chambers, and to the court reporter’s office. If the sidebar position provides a writing surface or shelf for the reporter’s use, it should be accessible.

Commentary:

Because the court reporter must interact with all participants in the courtroom, it is important that an accessible route connect the clerk’s station with the well, jury box, witness stand and other elements of the courtroom. Sight lines from the judge to all others in the courtroom should be maintained. The court reporter should have excellent sight lines to the judge, witness, attorneys, and other court participants. Proper positioning is critical and may require a secondary location for jury selection and side bar conferences.

Placement of the court reporter in respect to other stations will determine whether the court reporter’s station should be built-in or free-standing. Because the court reporter may have to move to several locations throughout the bench area in the course of proceedings, access to all areas in the courtroom well should be provided. In addition, the court reporter should be able to move from the courtroom workstation to the reporter’s office or to the judge’s chambers along an accessible path.

Common Errors:

- Integrating the court reporter’s station into the design while preserving sight lines and providing for wheelchair access is frequently not achieved.

- Designs fail to consider the normal duties and functions of the court reporter when planning for accessibility.

Applicable Guidelines:

Scoping:

206 or F206 Accessible Routes (including 206.2.4/ F206.2.4, Exception 1 concerning adaptability and 206.7.4/ F206.7.4 concerning the use of platform lifts)

231.2 or F231.2 Judicial Facilities/ Courtrooms

Technical:

Chapter 4 Accessible Routes

808 Courtrooms (sections 808.2 and 808.4)

902 Dining Surfaces and Work Surfaces

Furnishings

Counsel tables, lecterns, audio/visual carts and other common items in the courtroom may be fixed or non-fixed. Furnishings are commonly included in design plans and drawings, even when they are non-fixed. If they are fixed elements, they must comply with the ADA/ABA Guidelines. It is recommended that non-fixed elements be designed to meet the ADA/ABA Guidelines.

Counsel Tables

Minimum Requirements:

The surface of counsel tables must be between 28 and 34 inches above finished floor, with clearance for a person using a wheelchair to pull up to the tables. Counsel tables must have a minimum of 27 inches of vertical knee clearance under the table.

Recommendations for Best Practice:

- Tables with power operation to adjust the height should be provided.

- No apron should be provided under table to hinder knee clearance.

Commentary:

Adjustable tables provide for comfortable use by both people with and without disabilities.

Common Error:

Aprons around bottom of counsel tables often prevent a person using a wheelchair from pulling under the table.

Applicable Guidelines:

Scoping:

231.2 or F231.2 Judicial Facilities/ Courtrooms

Technical:

808.4 Judges’ Benches and Courtroom Stations

902 Dining Surfaces and Work Surfaces

Lecterns

Minimum Requirements:

Accessible work surfaces must be 28 inches minimum and 34 inches maximum above the floor. Knee and toe clearance must be provided. Clear floor space must be provided for a forward approach.

Recommendations for Best Practice:

- All users should be able to use the moveable lectern in the same manner. Lectern controls should be located within the range of motion of persons with disabilities. The ideal solution for the lectern is for the height and work surface to be adjustable to allow for optimum use.

- Lectern should be designed with a non-assisted (e.g. electric) lift mechanism to allow working heights from 28” to 44.” The top edge of the lectern should be adjustable with the work surface to allow an appropriate line of sight.

- Proper toe and knee clearances need to be provided.

- Work surface should be adjustable to different angles to allow a variety of uses.

- Adequate lighting should be provided on the podium to assist people with visual impairments.

- Controls should be easily accessible.

Figure: These lectern specifications provide forward approach access and an adjustable surface.

Figure: Accessible lectern with knee and toe clearance.

Commentary:

Lecterns can be custom-made and fabricated to be accessible. Accessible prefabricated lecterns are also available on the market.

Common Errors:

- Standard lecterns are too high for people who use wheelchairs or people of short stature.

- Lighting provided is typically inadequate for someone with a vision impairment to be able to see his/her paperwork adequately.

Applicable Guidelines:

Scoping:

205 or F205 Operable Parts

226 or F226 Dining Surfaces and Work Surfaces

Technical:

309 Operable Parts

902 Dining Surfaces and Work Surfaces

Audio Visual Carts

Minimum Requirements:

Audio / visual (AV) carts should be designed so that all user controls are within the reach range. All controls should be placed within accessible reach ranges, be operable with one hand, and not require tight grasping, pinching, or twisting of the wrist. If there is a work surface, it should be 28 inches minimum and 34 inches maximum above the floor.

Commentary:

The AV cart typically accommodates such devices as a computer, overhead projector or video camera, or DVD player.

Applicable Guidelines:

Scoping:

205 or F205 Operable Parts

Technical:

309 Operable Parts

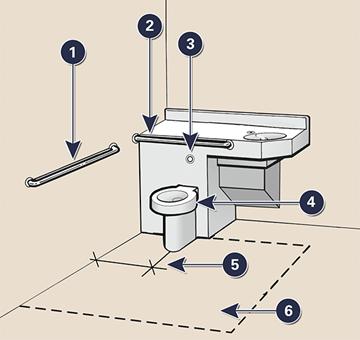

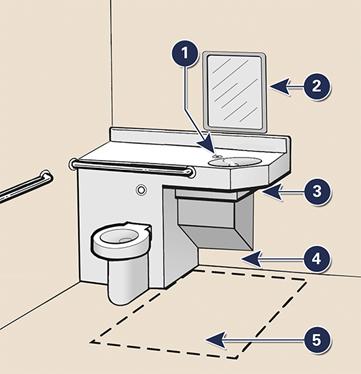

Judge’s Chambers

The design of judge’s chambers vary by courthouse. The chambers typically include the judge’s private office. They may include an outer office for the judge’s clerks, a reception area, a conference room and office work spaces. Some chambers include single occupant bathrooms and kitchenettes.

Minimum Requirements:

In state and local courts, areas used solely by the judge as a work area must provide accessible approach, entry, and exit. In Federal courthouses, they must be fully accessible. In both, public use areas within the judge’s chamber must be accessible. At least one accessible route shall connect to the accessible routes throughout the building. A person with a mobility impairment must be able to circulate throughout the spaces as well as approach, enter and exit from each office/workstation.

If a kitchenette/coffee area is provided, this area must be accessible. Access to the sink may be by a side approach or a front approach. The height for the rim of the sink is a maximum of 34 inches high.

If a bathroom is provided for the judge and his/her staff within the suite, this bathroom must be fully accessible. If the toilet room is available only for the judge and accessed through his/her private office, certain features are permitted to be adaptable.

Recommendations for Best Practice: